French New Wave and the Francois Truffaut's legacy

An investigation about The French New Wave and how its innovative, iconoclastic styles epitomizes in Francois Truffaut's Shoot the Piano Player

Shoot the Piano Player (Francois Truffaut, 1960), Truffaut’s second feature film may on the surface level may feel like a modest tale of crime thriller centering on pianist Charlie’s (Charles Aznavour) entanglement in a bizarre cat-and-mouse game. However, it is full of intimation and little eccentricities worthy of the viewers’ attention, crystalizing the spirit of the French New Wave.

The New Wave in Action

It is often noted how many of the directors within the New Wave made references to classic film movements and genres; so did Truffaut. For instance, the claustrophobic atmosphere stemmed from the chiaroscuro lighting schemes, and the dramatic shadow patterning right at the opening of the film is his direct tribute to the classic American noir films (1:50). Yet, this 4-min sequence is full of Truffaut’s acute implementation of salient New Wave stylistic elements. The scene starts with a chase sequence displaying Chico (Albert Remy) running for life from the two gangsters (Daniel Boulanger, Claude Mansard) pursuing. The interposition of shots of Chico sprinting and the car following with disoriented camera movements are the distinct language of the New Wave directors who knowingly twist temporal and spatial continuity. At the same time, Truffaut adopts the nonlinear storyline from neorealist films to play with the narrative a bit. While the viewers are still fixated on the thrilling chase sequence, in the next second Chico is stunned by a streetlight and soon gets rescued by a stranger (Alex Joffe) just passing by (2:37). Rather than return to Chico’s escape, for the next two minutes, the narrative digresses instead to capture Chico and the stranger having a casual conversation about life, love, and marriage. It is not until the stranger disappears at the corner (and never reappears in the rest of the film), the chase again carries on.

Still, the innovative editing and the episodic narrative structure are just one snippet of cinematic elements that Truffaut utilizes in Shoot the Piano Player. Followed by the wildly acclaimed debut The 400 Blows (Francois Truffaut, 1959), Truffaut continued to masterfully maneuver the frame to draw audiences’ attention to a specific point in the scene. In the final snowbound shootout with the gangsters (79:00), Lena (Marie Dubois) gets accidentally shot at on her way looking for Charlie. When Charlie finally shows up, everything is too late as Lena, covered in snow, has lost her breath already. As Charlie holds Lena with remorse, rather conventionally cut to a close-up of Lena’s face, Truffaut employs a combination of zoom shot and freeze-frame to immortalize this poignant moment, magnifying Charlie’s anguish in losing the beloved one.

Injections of Drollery

Truffaut takes the free-wheeling side of the French New Wave further by implementing gentle humor into his film even if the tone and subject matters can be quite intense. In the scene where Charlie and Lena have been kidnapped by the gangsters, for example, Truffaut turns a supposed agitated maneuver with the criminals into a waggish slapstick (25:30). Despite being kidnapped, Charlie and Lena keep having discussion apropos of driving, women, and sex with the two gangsters along the way, as if they have known each other for a long time. Then, noticing that the two gangsters have let down their guards, Lena pushes her foot on the drivers’s pedal in an attempt to get the car pulled over. The tactic is successful, allowing Charlie and Lena to walk away with ease while the gangsters have to end the kidnapping to deal with a passing traffic policeman. Interpolating these humorous aspects within the story again emphasizes the versatility and playfulness of this film alone.

Sometimes Shoot the Piano Player becomes reflexive as Truffaut reflects on the making of the film and makes flippant remarks about it. In an erotic scene where Charlie is about to enjoy himself for the rest of the night as Clarisse (Michele Mercier), already naked, is lying next to him (20:58), Charlie takes the bedsheet to cover Clarisse’s breast, joking “This is how it’s done in the movies.” Just like that, Truffaut, in sleight of hand, integrates his jocular comment about the classic Hollywood’s finicky Production Code, evincing his attitude towards the need for modern movies to disregard any forms of restriction.

Truffaut’s Brilliance

Besides, Truffaut did not apply all the cinematic elements of the French New Wave just for the sake of applying it; what really appeals to him in making the film is the sense of loneliness and alienation that is suggested for the protagonist. Charlie, a passe classical pianist, is portrayed as a diffident and reticent person who seems to be a little bit cut off from the rest of the world. In order to reflect such personality appropriately, Truffaut makes use of many New Wave stylistic devices, along with voiceovers and flashbacks, guiding the viewers into Charlie’s psyche. The voiceover is the most frequent and effective device that sheds light on Charlie’s subjective thoughts throughout the film. In particular, in the sequence where Charlie accompanies Lena back home right off the work (15:30), the close-ups of Charlie’s hand seeking to hold Lena’s is juxtaposed with shots of his restrained face. Such thoughtful editing is an apposite representation of Charlie’s lack of courage in taking initiatives, exemplifying his agitated state at the moment. The subsequent voiceover of Charlie searching for improvisations to break the silence once again directly demonstrates to the viewer Charlie’s reserved character.

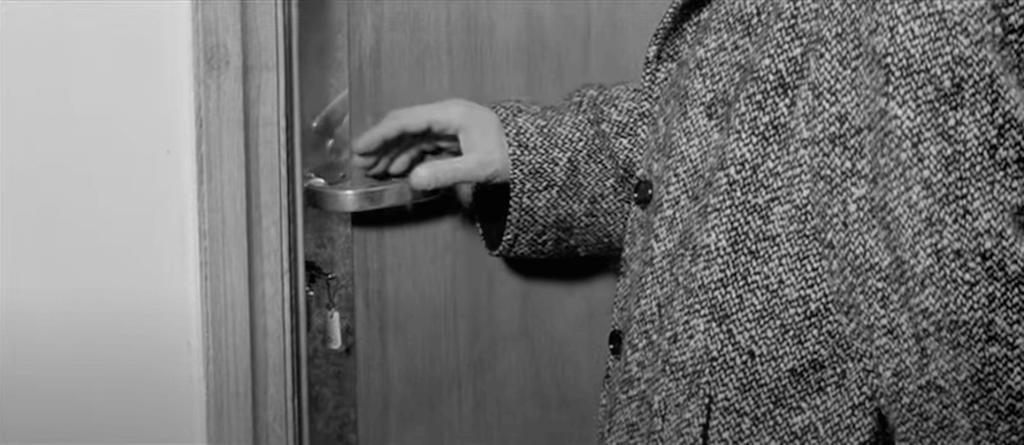

Another brilliant example of Truffaut’s keen link of visual style with the story’s idea and characterizations is the audition scene. Truffaut deliberately utilizes montage to call attention to Charlie’s psychology. As Charlie walks across the corridor and about to enter the audition room (33:53), first a medium close-up of Charlie playing with the door key is shown. Forthwith, we get three different close-ups of his finger teasing the door bell within different scales, and then a long shot from the end of the hall which completely jolts us back out again. The montage of Charlie’s hesitant actions plus the elongated corridor scene reinforce the idea of hollowness, as his ambivalent behavior keeps haunting him.

What’s more scintillating is that, in the next shot, the door is opened by a young lady who has just finished her audition. In most cases, we would expect the camera to follow Charlie entering the audition room and watching him performing in front of the judges. Surprisingly, the camera instead stays with this young lady, tracking back with her as she walks through the corridor and out of the building. Such an open-ended sequence epitomizes Truffaut’s mastery of the incidental narrative structure, and makes us wonder about his ulterior motif in creating it. Is he showing the lady because she might just be another victim of the sexual harassment just like Charlie’s dead wife, or because he simply wants to? By conscientiously incorporating stylistic features from the New Wave, meanwhile, blending his uptake of the modern cinema, Truffaut in harmony, creates an idiosyncratic film language that is distinct from any other coeval peers.