Animation and Its Relationship with Space

An analysis of Aylish Wood's journal Re-animating Space, and how The Adventures of Prince Ahmed, the first animation ever created, realizes her thesis

The notion of space, a familiar yet obscure concept, is often taken for granted by us for its universal presence. It is almost axiomatic that space is a quintessential component of our life and almost all activities in which we conduct involved some sort of interaction with space. In the daytime, we travel through the physical space to desire destinations, while in the nighttime, we navigate an illusory space in our dream where the most far-fetched fantasies exist. Even the databased footprints, text messages, phone calls, and contacts, that we leave when scrolling through our phone are being stored in an abstract space in case we want to visit again.

Space Role in Cinema

Despite the imperative role that space plays to justify our understanding of the world, the notion of space is frequently regarded as the most basic vehicle to sustain characters and narrative in a fictional realm built by its creator. As a result, we see conventional film-makers use the space, like a backdrop, downplaying it to the extent that can be indistinguishably blended with other cinematic elements to prevent viewers digress from the major progression of the narrative.

The appearance of animation, however, is deemed to overturn space’s neglected status and endow it with the capacity to draw connections to reality and crystalize the imaginative fantasy that cannot ever be imitated in live-action films. Aylish Wood, in her journal “Re-animating Space” advocates viewers to re-examine space, rather than a vessel passively containing events and characters, as an entity itself, an unbridled stream that brings disparate elements together, portraying each movement in harmony. In this short essay, I will primarily focus on analyzing Wood’s idea of “approaching space as an entity” with the use of The Adventures of Prince Ahmed (Lotte Reiniger, 1926) as the primary example accompanied by some references of other films to illustrate how the notion of space typifies in the animated space.

The Adventures of Prince Ahmed Groundbreaking Approach to Space

The term “reverberation” that Woods brings forth is central to her theory of re-animating space - soliciting attention to the metamorphosis and the continuity that space brings about in cinema. “Reverberation of space,” an undergoing process that is “existing beyond the location of events, fluid and marked by heterogeneity, shifting between familiarity and uncertainty, and finally as chaotic and potentially unknowable.,”(29) can be identified as three distinct features — unexpectedness in transition/metamorphosis, heterogeneity in elements, and multiplicity in meaning, that each says something about animation’s ability to enliven space in a virtual realm.

Aforementioned, space’s objectivity and accountability make it an apposite resort for viewers to rationalize the environment established by live-actions. We use space as a reference to locations and time in frames, and in return we justify the characters’ actions and motivations.

To understand space as an independent body, however, Woods proposes a drastic shift from such conventional views and argues that space is, in essence, transformative and thus unexpected. Unlike conventional film-making which strives to maintain consistency between cuts of different spaces, animators have extensive latitude in manipulating and distorting space to achieve their whimsical ideas, playing with the viewer’s expectation in respect of the narrative. Boundaries between different dimensions are constantly being crossed and are interconnected through seamless action/graphic matches as we see in the opening four minutes of Paprika (Satoshi Kon, 2006) and the incessant metamorphosis of space and time in The Street (Caroline Leaf, 1976.)

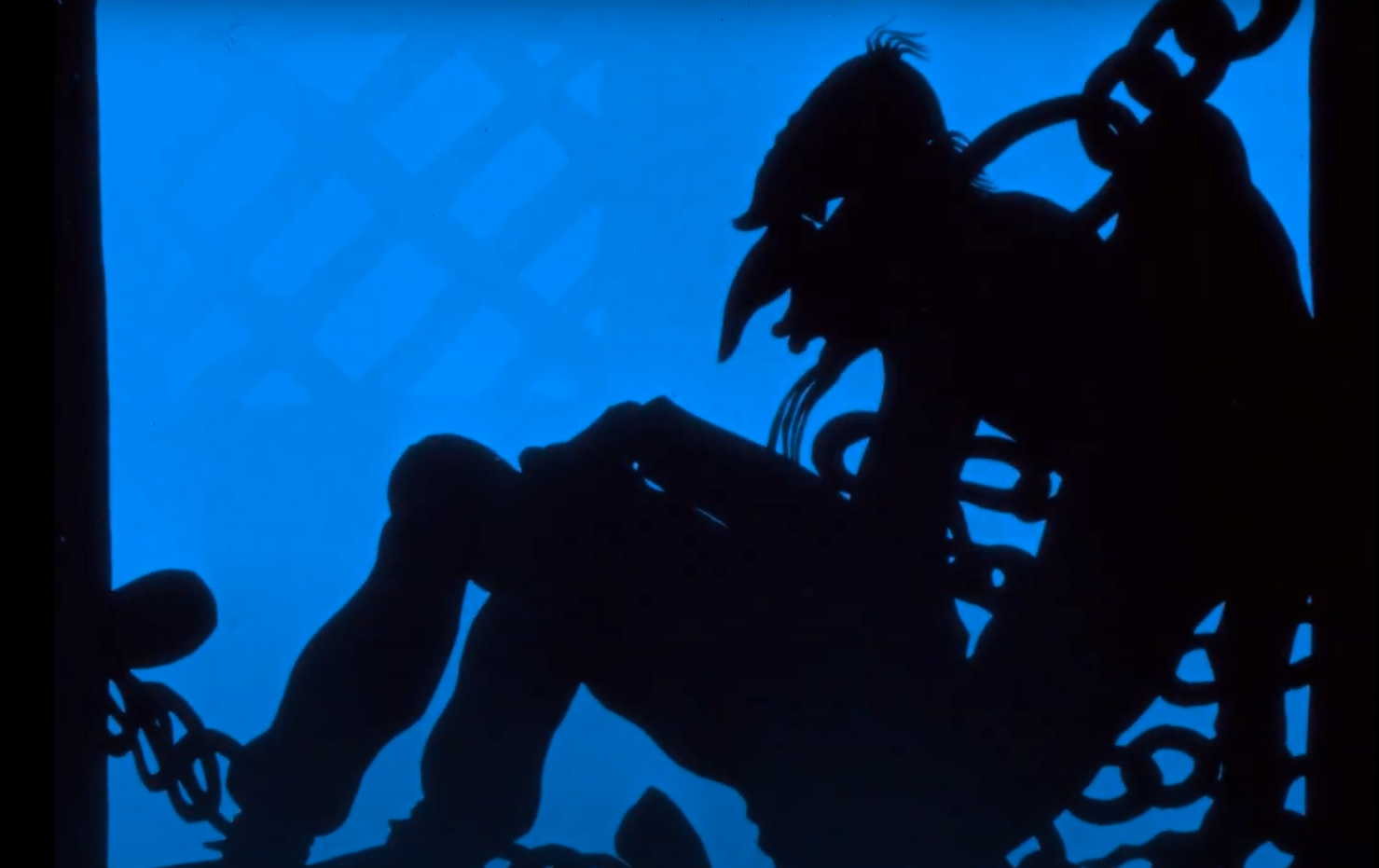

Such unexpected use of space, too, occurs in The Adventures of Prince Ahmed. In the prison where the African magician is captured, the space is initially a two-dimensional one with only the magician, being fully chained, despondently sitting on the ground. Although the general setting does not entail any clues of how he can escape from the claustrophobic cell, as the plot advanced, the frame starts transforming into a three-dimensional space, revealing the tiny window that is once obscurely situated at the back. The augmentation of the space’s dimension and the depth of fields offers an outlet for the magician’s escape, as he turns himself into a bat and ultimately flies out of the window after being informed about Prince Ahmed’s affair with Pari Banu.

The perpetuating movement of space in both the recognizable and the concealed territories generates a sense of disorientation, inviting viewers to adjust and make connections between the spatial discontinuities. (30)

The Hybrid Nature of Space

Granted that the space should be treated as a sole entity, it is not to say that the existence of space is mutually exclusive, like a monolith that resists inclusion in other elements. Just the opposite, Woods asserts that space can be heterogeneous and fluid as well, quoting that the process of spatiality is “not simply to be the place of singular events, but an assembly of different habitations creating multifaceted spaces.”(32) It is at a triadic rapport with character and action that space fluidly ties disparate components unobtrusively. Woods ascribes the idiosyncratic film-making techniques as a cornerstone to construct fluid spatiality in animation.

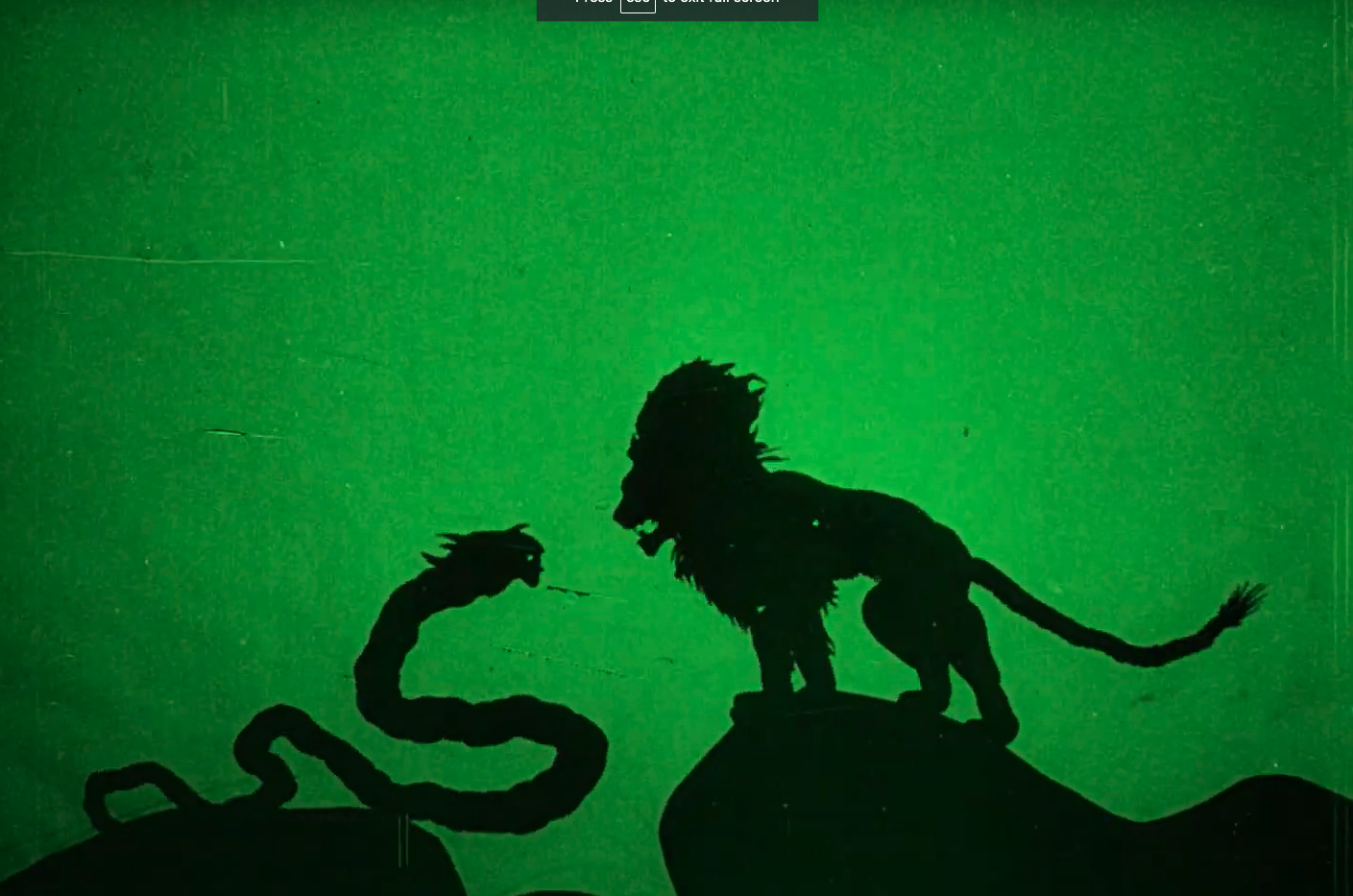

Similar to Caroline Leaf’s uses of sand and oil paint to intermingle with space and time, The Adventures of Prince Ahmed’s rich visual language relies on Reiniger’s eminent scissor works, cutting paper into intricate silhouettes and using them for shadow puppetry. As the film is all told through shapes, the engagement with viewers is from the way that the characters and environments are cut out. Every figure is not only unique by its shapes, but also exhibits an illusion of texture where the cuts are so precious to bring out such details on the leaves, the feathers, and the outfits. What’s more, the cuts will go into the character to show their faces and facial expression, revealing what they are thinking at the moment. The subtlety of the figures’ movement further exemplifies the film’s close tie with space where they can move around in a broad and dramatized manner or in a small and barely noticeable way to present more in terms of the character’s psyche.

On top of incorporating an exquisite art style, the film holds some seemingly violent scenes that also manifest the fluid spatiality. One of the scenes that focalize such characteristic is the fighting sequences where African Magician battles with the Witch as they transform into different creatures that have their own functions and how they can pose threats along with their use. While the ever-evolving shapes of the monsters offer an uncanny approach to illustrate a battle sequence, the shapes themselves implicitly impart shifting dynamic of the two’s duel as they strategically switch their forms to hold against another.

Absence of Space

Although one may be entirely captivated by the labyrinthine filigree cutting that Reiniger creates, one aspect of The Adventures of Prince Ahmed’s twist of space to convey ideas lies in the absence of the space. Just as Woods encourages viewers to think about space when it is not “used-up,”(31) one would surprise to see how in-depth the figures are embodied in these two-dimensional black cutouts. Each character is considered an active, eloquent being when they move through the animated space, but at the same time, the silhouette animation leaves just enough space for our brain to supplement what is given, sparking new interpretation apropos of the scenarios presented.

The theme of absence that we fill with our imagination in terms of what we see leads to Wood’s final point about the multiplicity stemming from the reverberation of space in which “a given spatial organization reconfigures space, forcing the re-discovery that what is mapped out through familiarity is only dimension of a multiplicity of possibilities.”(33) The aesthetic of The Adventures of Prince Ahmed is essentially a mix of realism and avant-garde abstraction. The special effects, like ocean waves, starlit skies, and most noticeably all the magic spells, play a crucial role to not only add physical layers (depth of field) onto the scene but bestow a metaphysical layer that is beyond our stereotypical world images.

Towards the end of the film, the witch lights up the magic lamp after a landslide victory over the devil. The emitting light, despite its intangibility, disseminates across the whole screen, bringing nothing but warmth and hope. Let alone a direct indication of a consummate finale, the lamp’s symbolic implication is salient in that it is an analogy of the pervasiveness of space, imbued with inspirational ideas and layers of meaning. In addition to the special effects, Reiniger’s deliberate employment of color (tinting/toning) to visually epitomize space as a boundless entity is equally sensational. Reminiscent of the visual language from German Expressionism, Reiniger injects color to planes in particular ways that form a prismatic relationship to the milieu of time and moods. The red or various shades of red could be an erotic scene or as a symbol of danger while blue may be a representation of nights. The vibrant color palette adds the finishing touch to the film’s mythical leitmotif, allowing viewers to not only see, but sense the multidimensionality of animated space.

Final Words

To finish, Woods recapitulates her idea in which “space seized upon by the imaginative possibilities of animation.”(45) We each experience reality and fantasy at the same time as individuals, and also collectively as a society. Reiniger’s evocative animation, just like the free-wheeling spatiality within, is an attempt to depict such phenomenon in silhouettes and fluid movements. In the course of almost a century, animation pushes our understanding of space and time in ways that are not considered viable in live-actions. Not just because its imaginative spirit, but through elastic approaches to engage with the audience — a unique way to move from the consciousness to the unconsciousness.