Early Soviet Montage Movement

A brief discussion about early Soviet montage movement & comparisons of montage employment between Pudovkin and Eisenstein

Introduction

During the Montage movement, Soviet films were relatively similar in terms of genres. As Lenin declared, “Of all the arts, for us the cinema is the most important,” (Bordwell, 107) The Bolshevik regime realized that the cinema was the most powerful tool for propaganda and education, given the 80% rates of illiteracy and the mix of vernaculars straddled across the country. Hence, we could see a great similarity in films directed by most of the Montage directors during that time. Depictions of uprisings, strikes, and rebellion against the authoritarian regime were extremely popular among directors who emphasized the Bolshevik ideology in films.

Both Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein, 1925) and Mother (Pudovkin, 1926) include various strikes and demonstration sequences to highlight the tension between the authorities and civilians, commemorating the failed Revolution of 1905. In order to be as comprehensible to the viewers as possible, intertitles in both Mother and Battleship Potemkin were simple and concise. Phrases like “It was spring”, “Even a dog wouldn’t eat this”, and “Brothers!” helped to maintain the continuity in the narratives, but also powerful enough to evoke the spectator’s emotion about the Bolsheviks’ solidarity in the revolution.

Pudovkin and Eisenstein

Pudovkin

As Bordwell points out in Film History, “…it [montage] also served more abstract purposes, linking two actions for the sake of a thematic point.” (117) The use of montage to construct narrative and court spectators’ attention was prevalent among Soviets directors, and Pudovkin and Eisenstein are prime examples. Despite their consensus on the search for dynamism through montage, Pudovkin and Eisenstein, however, diverged drastically regarding the role which montage played in film narration. Greatly influenced by Kuleshov, Pudovkin inherited the idea of continuity editing from Hollywood, in which filmmaker created an immersive experience for the viewer to match reality in a natural way. Pointed out by Pudovkin in his Selected Essays, “The director despotically manipulate the viewer’s attention. The viewer sees only what the director shows him”(35). He stressed the use of montage to achieve the “the maximum simplicity”(36) and “clarity in resolving each individual problem”(36) when constructing a sequence.

In the first sequence of Mother, when the mother (Vera Baranovskaya) is being abused by the alcoholic husband (Aleksandr Chistyakov), Pudovkin employed techniques like match-on-action and eye-line matches to cut between numerous shots to highlight each protagonist’s personality, but also intelligibly establish the family dynamics with little explanation. The back-and-forth cuts of father and the son (Nikolay Batalov) and respective close-ups of the hammer and the father’s clenched hands, captures the family’s extreme tension and the son’s resolution to protect his mother. Reminiscent of the last-minute rescue sequence in The Birth of a Nation (D. W. Griffith, 1915), the crosscutting between the prison riot and the protest march in the last sequence of Mother, helps to build up the final culmination, and captivate the audience’s attention in a state of intense excitement.

Eisenstein

Rather than paying excessive attention to maintain a comprehensible narrative like Pudovkin, Eisenstein was more radical and more experimental in terms of what montage could achieve. In his theory of film, Eisenstein often brought up the term “conflict” in which “antithetical elements clash and produce a synthesis that goes beyond both.” (Bordwell, 113) Eisenstein did not see montage as a resort to maintain a clear temporal and spatial relationship, guiding the spectator through the entire narrative. Rather he envisioned each individual shot or sequence as if it was a puzzle with meanings of their own. When combined, however, these individual shots created an utterly different picture, sparking new meaning that was not present in either of the original shots.

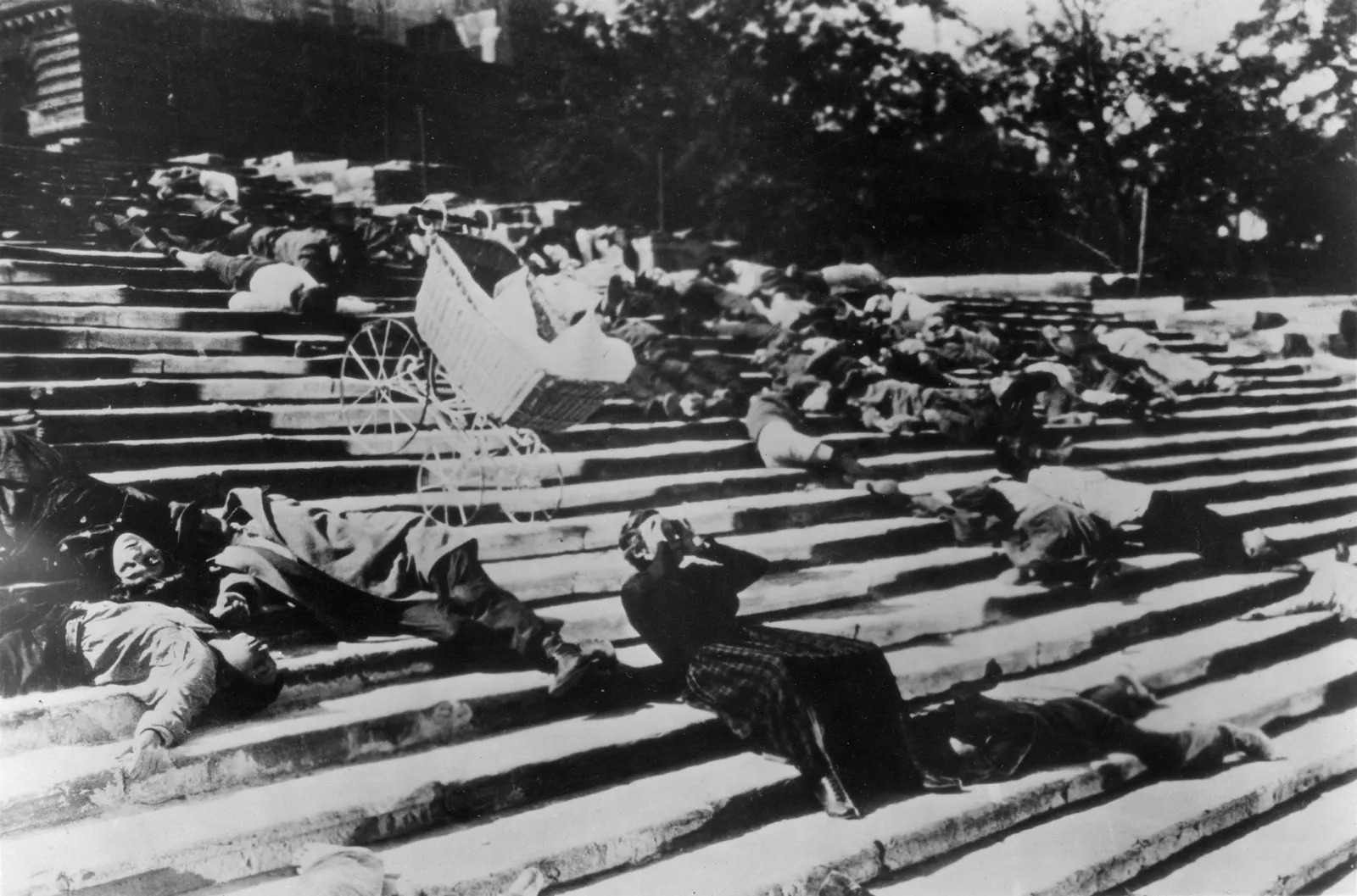

The infamous Odessa stairs sequence in Battleship Potemkin is the moment when Eisenstein fully actualizes his “intellectual montage” theory. Shots of soldiers marching down steps symbolize an oppressive force juxtaposed with unarmed civilians fleeing, barring the straightforward indication of the helplessness of the Russian people, offers new meanings of the Russian Empire’s forces’ brutality. The last sequence of the Odessa massacre constitutes shots of the stroller sliding downstairs across dead bodies, the slaughter of civilians, and close-ups of a woman’s face, covered with blood. Albeit the considerable lack of spatial and temporal relation, the sequence’s short and sharp intercuts epitomize the agony of innocuous civilians, insinuating the viciousness of the Russian army. Besides, Eisenstein deliberately intercuts three consecutive shots of stone lion statues when illustrating the bombardment of the Odess theater. Although shots of the lion may not mean much on their own, when combined, it seems like the lion is rising from its sleep. They signify the Odessa people waking up and fighting against the totalitarian regime and seemingly paralleled with the first half of the film, where asleep crews ignite the revolution on battleship Potemkin.

Final Thoughts

At the beginning of the 1930s, audiences, who were tired of the esoteric style of montage, began to demand for something more accessible and more evocative. Along with the permeation of series of Socialist Realism films which focus on realistic stories that supported Communist values, the Soviet Montage movement eventually came to an end. Like many revolutionary cinema movements, however, techniques by the Soviet Montage filmmakers continue to influence movies, such as Rear Window (Alfred Hitchcock, 1954) and The Godfather (Francis Ford Coppola, 1972), to this day.