Thoughts on "Cinemas of Attraction"

An excerpt and a reflection about "Cinemas of Attraction" by Tom Gunning

In the essay “The Cinema of Attraction,” Gunning made a clear distinction between early theatrical cinema and early narrative films using 1906 as the defining year. He argued that instead of focusing on cinema as a medium that conveyed a sense of logical narratives, early films (prior to 1906) were simply created as a tool for amusements and novelties, which he later defined as “the cinema of attractions.”

Inspired by Eisenstein’s “Montage of Attractions” essay, Gunning believed that attractions provoked spectators’ sensual and psychological reactions. The prime goal of early cinema is to proffer such magical illusions to the broad audiences, and all the cinematography and editing techniques utilized (tricks) are for the sole intention to solicit such attention out of them.

Gunning credited two significant utilization of attractions in the early cinema. He pointed out that a sense of “actuality” played a crucial role in films before 1906 and is preponderance over narrative films in terms of production. The Lumière Brother, who according to Gunning created films that engage in “placing the world within one’s reach,” were dedicated to provide the most realistic visual sensations to the spectators. Both Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat (1895) and The Sprinkler Sprinkled (1895) simply filmed as a documentary of everyday scenes, however, audiences were still amazed not virtually because of the narration or the theatrical elements but films’ visibility and the exhibited nature.

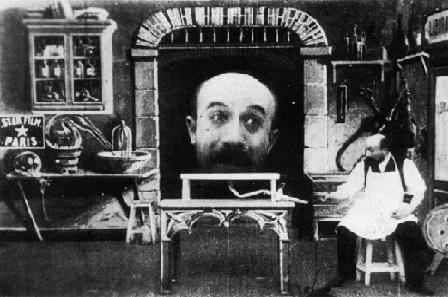

Méliès, born as a magician, had an even deeper uptake of how films could create such illusory moments for occupying spectators’ attention. Méliès never intended to hide his passion for adopting “tricks” in films. His talented editing skills allowed him to add special effects (making heads disappear, a lady suddenly vanish on the stage) freely in the course of production in films like The Four Troublesome Heads (1898) and The Man with The Rubber Head (1901). Along with his clownish performances, Méliès was again able to put on a pompous show to galvanize the crowd’s reaction, but this time in films. In some of his creations, for instance, Voyage to the Moon (1902), he indeed demonstrated traits of plots, adoptions of traditional theatre, and even repeated actions in two successive shots which were thought to be one of the major signs of continuous, logical narration. Gunning, however, was not totally convinced and went ahead argued that the noticeable underlying narrative structures underlay in Méliès’s films were flagged as being of second or third order importance. They served as a framework for Méliès to fully exhibit his magical effects and tricks in front of the crowd, instead of a standalone entity which would possibly alter spectators’ preexisting perception of films.

Gunning went further and discredited the neglect of the importance of narrative in the early cinemas by accentuated the fact that technology, not film itself was the imposing attraction. With the existence of the kinetograph, and the nascence of more advanced filming technologies, film creators virtually had neither intentions nor motivations to rigorously work on a self-sufficient plot but often left the film projector itself to do all the talking. Gunning likened going to a traditional film theatre in the past to visit a fairground, which people were enthralled by the latest technological marvel and films were just happened to be the medium of display. Exhibitors would even re-edit the originals by adding sound effects, commentaries to maximize spectators’ corporeal pleasures while soliciting the attention of them.

Despite impugning early cinema as merely an implement of courting attention from the mass, Cunning did credit the film creators’ endeavor to maintain a holistic narrative structure. Cunning described these efforts as “ambiguous,” and mentioned Porter’s The Great Train Robbery (1903) as an example. While the robbery story accompanied copious violent actions in the film along with the infamous final close up shot of an outlaw firing further reinforced the point on captivating attention of spectators, Gunning acknowledged Porter’s industry for retaining consistency on continuity. In alignment with Cunning, in the book ”Film History, An Introduction”, Thompson and Bordwell also highlighted Porter as one of the forerunners in creating plot-driven and continuous films. Whether was the employments of repeated actions in Life of an American Fireman (1903) adopted from Méliès or the utilizations of crossing cutting he invented in The Great Train Robbery, Porter’s contribution toward the emergence of continuity editing was undeniable.

Finally, Gunning gave out his thoughts on the development of cinema by writing down an incisive claim when approaching to the end of the essay — “Every change in film history implies a change in its address to the spectator, and each period constructs its spectator in a new way.”(8)