Bicycle Thieves & De Sica' episodic narrative structure

A short analysis on the episodic narrative structure of the classic Italian Neorealists film - Bicycle Thieves

Introduction

In his essay about Bicycle Thieves (De Sica, 1948), Andre Bazin makes a jocular comment in terms of the film’s simple narrative, “Plainly there is not enough material here even for a news item: the whole story would not deserve two lines in a stray-dog column.” (Bazin, 50) Indeed when examining the entire film, Bicycle Thieves seemingly advances in chronological order, telling a story of Antonio Ricci (Lamberto Maggiorani), an unemployed man desperately searching for his stolen bike in a two-day span. However, De Sica, in both the uses of linear and episodic narrative structures, earnestly create one of the most wondrous and heart-rending masterpieces, portraying the vicissitude of a person living in post-WWII Italy.

A Simple Story about Father and Son

In the majority of Hollywood productions, the characters in film often have sets of goals or deadlines (this is often called continuous editing). All the events that occur in the film are designed to advance the plot to meet these goals and achieve a consummate finale. The same logical narrative structure also applies to Bicycle Thieves. Like the film title suggests, the whole film’s narrative settles around the bicycle. Throughout the film, Ricci’s actions and behaviors are mostly driven by his motivation to recover his beloved bicycle. And we can see a clear linear causal logic in the narrative structure just at the beginning, establishing the cause and setting the goal of the film.

As the film starts, we follow a medium shot of a bus stopping by the unemployment office with a crowd of job seekers rushing to the gate, longing for the slightest chance of securing a position. Along with the movement of a worker leaving the crowd yelling for Ricci, the scene is cut to a panoramic shot, establishing the temporal space surrounded for the first time . Despite having lost faith in job searching, Ricci is fortuitous enough to procure a job of pasting posters among the massive unemployed, but a bicycle is a requisite to secure the position. Henceforth, a dissolve transition leads us to the next scene, where Ricci is walking backed home with his wife, Maria (Lianella Carell), informing her about the dilemma he faces. Considering that it is a luxury for Ricci to secure a job, notwithstanding the indigent status, they decide to sell their bedsheets to earn the money for the bike. Just as Maria begins to wash the sheets and getting them ready to impawn, at the very next shot, the scene has already dissolved to the pawnshop where Maria is bargaining with the staff, begging to trade the sheets for a better price.

With all the sacrifices, Ricci finally gets what he has dreamed of, a bicycle that allows him to support his family of four. With his beloved bicycle, in the next sequence, Ricci arrives forthwith at the employment office to register to be an official poster hanger. From firstly securing the job, and being notified about the prerequisite, to the family having to trade the bedsheets for the bicycle, until finally Ricci acquires the job in the employment office, the very beginning of Bicycle Thieves rigorously follows a linear, causal narrative structure. In a mere 10 minutes length, De Sica adapts continuous editing to outline the general context of Ricci and his bicycle in a logical and succinct manner.

The episodic narrative takes over

It is ostensibly a simple plot if we only choose to look at the first 20 minutes of Bicycle Thieves. However, as Ricci’s bike is stolen and he starts the fruitless search, the episodic approach to story-telling, from time to time, supplants the causal narrative as an alternative mean to advance the narrative till the end. “The film unfolds on the level of accident” (Bazin, 59). Bazin’s words shed light on the involuntary nature of De Sica’s episodic narration. The hopeless search of the father and the son (Enzo Staiola) happens very naturally, as they meandering in the city of Rome with no particular destinations in mind. The film takes us to multiple spots through the two’s search: the union gathering, the police station, the spare parts market, the seer, and the church, some are for the sake of looking for the stolen bike while others are virtually out of spontaneity. Nonetheless, we are forced to follow the lens to observe, to feel the tension and the struggle of the bottom of the society without the film explicitly spelling it out for the audience.

The scene where Ricci and Bruno shelter from the rain is a classic exemplar of De Sica’s dedramatized approach to the narrative. Just as Ricci and Bruno are on the way to another spare parts market, a pouring rain interrupts their miserable search. Several long shots firstly illustrate them standing in the rain at a loss, as people and vendors are fleeing for shelter. Then the scene cuts to the close-up shots, as Ricci wandering, keeping Bruno by his side, anxiously looking for any possible traces of his stolen bike. Just when the rain gets heavier and heavier, in despair, Ricci and Bruno decide to halt the search momentarily and shelter under a roof. A span of 2-minutes shelter scene begins with a brief conversation between the two about Ricci’s inadvertent behavior to his son. Then, out of nowhere, a group of foreign seminarians comes to the roof for shelter. They speak an utterly different language (there are not any subtitles given). Interestingly, however, De Sica did not immediately cut to the next scene where the rain is already over. Instead, we are just as trapped and confused as Ricci and Bruno, being forced to spend time listening to the querulous chatters till the rain is over.

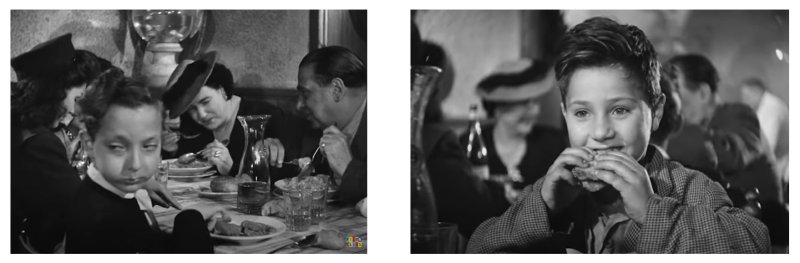

Another salient example of De Sica’s brilliant episodic narration is the restaurant scene. After an irresponsible reprimand to Bruno and having feared that he has drowned, Ricci finally realizes his obliviousness to his son that all this time his focus is just to find the bicycle, because of how much the it means to him. To make up for the previous impropriety, Ricci promises Bruno to have a feast and go home afterward, forgetting about the search for a moment. When Ricci and Bruno walk into a restaurant, they order mozzarellas and wine as if it is a celebration. It seems like Ricci decides to move on and the story again is heading toward a positive direction. However, Ricci and Bruno are accidentally assigned to a table right next to an opulent family who is having a feast. The multiple back-and-forth cuts of the family’s gluttony as oppose to their simple courses set as a constant remainder to Ricci the indispensable role that money plays in reality. Being pulled back from the fantasy, Ricci realized that the bicycle is the last and only resort to make his family eat again, and he is going to take any means necessary to retrieve it.

Final Thoughts

When an American producer told Zavattini that “Hollywood film would show a plane passing overhead, then machine-gun fire, then the plane falling out of the sky but that a Neorealist film would show the plane passing once, then again, then again,” Zavattini replied “It is not enough to have the plane pass by three times; it must pass by twenty times” (T&B, 325). Unlike Bicycle Thieves’s heavy emphasis on the episodic and accidental narrative structure, classical Hollywood productions, like Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1942), relied on frequent cuttings and editing to downplay the episodic elements. In doing so, the film can put the focus on the main cause of the story, avoiding any possible distractions and impediments and ultimately offering audiences the perceived perfect ending.

“The (search) events are not necessarily signs of something, of a truth of which we are to be convinced, they all carry their own weight, their complete uniqueness, that ambiguity that characterizes any fact”(Bazin, 52). Just as Bazin suggested, by cleverly adding independent accidents along the narrative, it is ambiguous in terms of what exact message Bicycle Thieves wants to send to the audiences. Some audiences might be drawn into the film’s indictment for inequality which permeates the post-WW2 Italian society, while others are affected by the in-depth portrait of father-son power dynamics or the trenchant depiction of religion’s sanctimoniousness. But does it matter? At the end, when Ricci and Bruno disappear into the masses, their story has become part of our story. And what we might see as something personal has become universal.