Paris Is Burning

A commentary about Paris Is Burning, a documentary about NY's queer community in the 90s.

“You have three strikes against you in this world, every black man has two - that they are just black and they are male - but you are black and you are male and you are gay.” As one of the voguers suggests at the very beginning, the film reveals the anguish and hardship for black queers to sustain themselves in a world filled with homophobia, transphobia, racism, and poverty. If football and basketball are competitions that make straight people crazy, then the ball is African American queers’ Carnival. It constitutes the narrative of the documentary, and epitomizes the New York City’s queer community’s way of living.

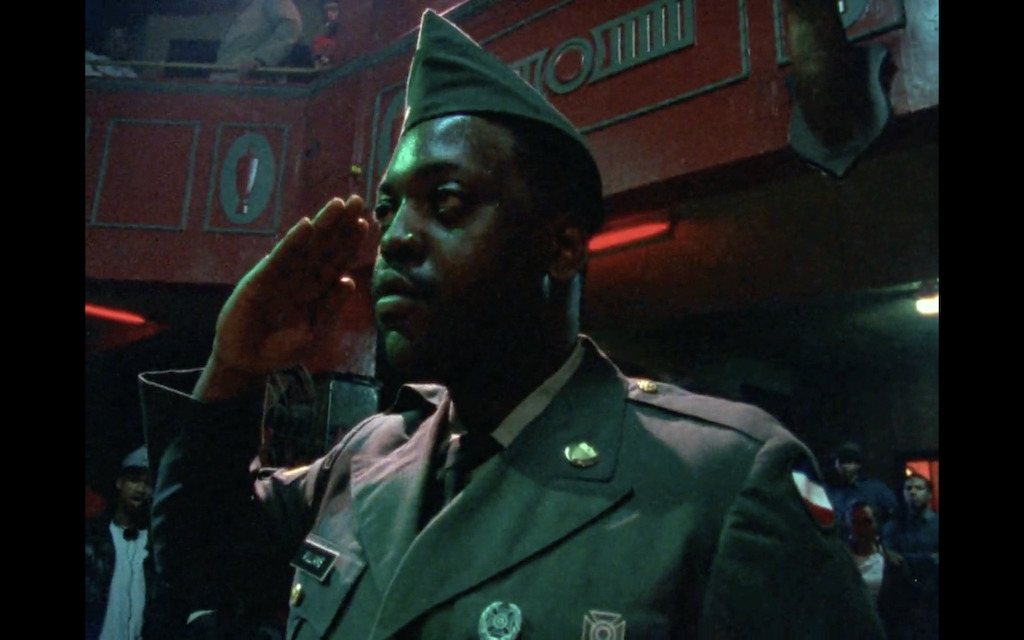

The ball refers to a sumptuous but competitive celebration of identity and spirit in the 1980s. The competition is divided into several categories, including mimics of fashion house walk shows, vogue (a style of dancing) competitions, and role playing. People from every corner of the city gather in the ballroom in the most splendid manner to compete, aspiring to bring the “house” down. Every ball is about being real to each other’s identity and at the same time achieve fantasies that would not ever come true in real life. People who are never going to get a job as a corporate executive are wearing formal suits, with cigars in their mouths, walking across the room like they are hurrying to work in Wall Street. Girls who work in the corner stores in your neighborhood can appear fabulously, walking down the ballroom like they are on the runway of the Paris fashion house. Although ephemeral, these vivid performances actualize the fantasy that voguers have been longed for.

In the ball, candor and genuineness are two things that matter the most. People can express emotions and desires without withholding their true identities. While the ball emphasizes individualism, “house” begins to emerge as the ball and the vogue evolve into a prevalent subculture in the city. Founded by some of the drag-ball veterans, the “house” signifies family and as a shelter, offering sustenance for “children” who share close aesthetic tastes and deep emotional connections, regardless of their races, identities, or social standing. “LaBeija,” “Ninja,” “Xtravaganza,” kids are willing to forfeit their original family name, and join the “house” as one part of the family. Rivals battle against each other not only for the final grand prize, but the glory of the “house” they represent.

Just like the flip side of a coin, behind the intimate and splendor drag-ball scene, however, underlies the anguish and struggles of the queer community, suffering from social prejudice and discrimination from the society. Behind the growth of each “house” is the rising number of children ousted and abandoned by their original families. Displaced kids would come to the ball starving with nothing in their pockets, searching for pleasure, excitement, and most importantly escape from the reality filled with hatred. Kids would steal things to get them to dress up, and come to a ball and live their fantasies for one night. “Girls” are willing to prostitute themselves to fund their transgender surgeries in order to become the most salient star in the ball and make their “family” proud. For many of the participants, the ball is no longer a dreamland, passing over love and positive energy, but highly addictive. It creates a vicious circle in which participants would virtually do anything just for a transient moment of indulgence.

Venus Xtravaganza, one of the most tragic figures in the film, is a transgender who aspires to become a star/model, and pines for the social approval of the mass. Like typical teenage girls, she envies spoiled, rich, white girls living lavish lives without worrying to sustain themselves. She dreams to be loved by someone, and lives somewhere far away, where no one can identify her. However, as Venus about to work herself out of the mud, her dream shattered just two years before the premiere of Paris Is Burning as her body was uncovered under a bed in a sleazy hotel four days after being brutally strangled.

Venus’s death is just a snippet of the predicament that the African American queer community encountered. Paris Is Burning did a great job in portraying the positive and idealistic side of the drag-ball, but still cannot cover up the cruelty and the indifference that the queer community faced in the reality. At the end of the documentary, voguers finally have an opportunity to display their performances on televisions, music videos, and even fly to Paris to walk on the fashion runway. However, the crowds surrounded them are no longer the congenial “family member” like it used to be, but groups of secular spectators searching for entertainment and senses of novelty. Vogue dance, together with underground drag culture, has been cited as the epitome of the decadent and depressing youth culture in the 80s, and those aspiring youths who dedicate themselves to participating in this spectacle have become just another appealing conversation over the dinner table.