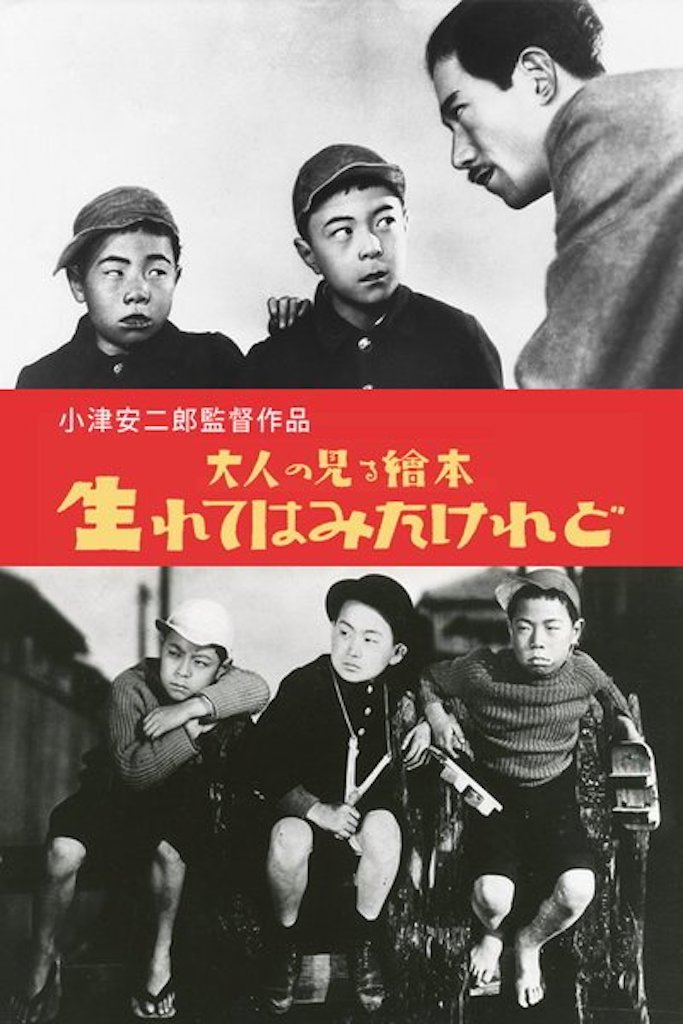

I was Born, But...

A commentary about Yasujiro Ozu's aptitude in parallel narrative structure, cinematography & 360 degree system in the film I was Born, But...

Narrative

I Was Born, But… revolves around the notion of power. For salarymen like Yoshii, all the powers concentrate on the hands of the Iwasaki (Takeshi Sakamoto), the big executive in charge of the firm. In order to receive a good salary, and afford a better life for the family, Yoshii racks his mind to hobnob with his boss. Regardless of the physical locations, he would approach Iwasaki in an adulatory manner whenever he has a chance, to not only physically, but mentally live near the boss. Knowing Iwasaki’s passion for film, Yoshii even participates in Iwasaki’s filming of daily vignettes to cater for his interest, which will later trigger a galling incidence, provoking a series of family dramas. While Ozu revealed a bleak image of underlying hierarchies in the adult world and the hypocritical social fabric embedded in the system, he presented a rather humorous and frisky plot via the scope of the neighborhood children, paralleling with the salaryman script.

Unlike the adult world brimming with intrigues and office politics, for children, the advent of power lies in physical strength. New to the neighborhood, Ryoichi and Keiji struggle to blend in the new environment, especially when they are intimidated by school bullies, led by a bigger kid (Zentaro Iijima). Luckily, they are wise enough to exploit the physical power of the older delivery boy (Shoichi Kofujita), and eventually to supersede the bigger kid as the most dominant figures in the neighborhood. Even Taro (Katô), Iwasaki’s son, has to pay deference to the boys’ incantation. (a game often played among the children)

In the sequence in which the kids witness Yoshii accompanying Iwasaki back home, we finally see these two storylines interweave. Ashamed of the fact that Taro’s father is their father’s boss, Ryoichi and Keiji once again cast the incantation on Toro, hoping to regain at least part of their supremacy. However, Yoshii intervenes and halts the game forthwith, helping Taro gets up from the ground as if he is treating his boss at work at the same time reproaching his sons’ impropriety. Of course, the twins would not understand why their father, an undisputed hero figure in their opinion, would treat Taro in such an obsequious manner. Nevertheless, Father’s reprimand is a blow to the brothers’ imaginary fantasy, offering them a snippet of the how things should work in the reality. The scene puts the two independent worlds under the same frame, revealing adult society’s boot-licking conducts as oppose to children’s ingenuous power ideology and imparting them an imperative lesson about the rigid stratification of the society for the first time.

Camera Movement

Ozu’s deft camera movements usage are inalienable from narrative functions achieved in I Was Born, But… Nonetheless, the most salient visual style ought to be his utilization of camera movements as a medium to navigate between the two major storylines. Reminiscent of Fritz Lang’s employment of sound as a cue to cut between different spaces in M, (Fritz Lang, 1931), Ozu harnessed the tracking of the camera to establish a relationship between two shots regardless of the discontinuous spaces.

In the playground/office scene, a sequence of students marching down the playground is cut to the father’s office smoothly as the camera tracks from left to right. The playful camera movement proffers a sense of verisimilitude as audiences mentally follow the camera motion, navigating between the two settings despite the lack of temporal unity. The juxtaposition of irrelevant sequences also puts two drastically different worlds (children and adults) in compare and contrast with each other, soliciting viewers’ examination of the ulterior motifs behind the image. On the playground, the bigger kid got excoriated by the teacher for not following instructions like other students do. In a cut to the next sequence, the camera, however, now tracking from left to right, capturing an associate who meant to concentrate on work, and shifts right forthwith as he could not resist the soporific working environment and began to yawn like anyone else. These nuances in each character’s synchronous motions allude to the social conformity which everyone ought to obey, epitomizing the foreboding transition from carefree children to institutionalized worker for each person living in the society surrounded by sheer competition.

The 360 Degree System

Although taking immense amounts of inspiration from classical Hollywood comedy, Ozu repeatedly violated the Hollywood continuity editing principle. Instead filming the dialogue scene in the traditional over-the-shoulder method, Ozu framed his dialogue scene more often in a 360-degree style, constantly switching camera positions, proffering a discordant but holistic scene.

In the film’s final scene, after understanding the father’s identity and accepting the reality of the life, the two brothers admitted Taro’s father is indeed better. After reconciliation, a straight-on medium long shot shows that the brothers again casting incantation on Taro. In the next shot, however, the camera has already moved behind Ryoichi’s feet, as we observe Taro’s “death” on the ground. At the moment that Ryoichi and Keiji cast the second “revival” incantation in the subsequent shot, the camera has completely switched to the opposite point of view that the initial shot is at, revealing not only the twin brothers but also the train rail barrier.

People would often associate discontinuity film production such as 360-degree system, uncanny camera positions, and playful editing with a sense of distance and detachment because of the diminishing effect on the temporal unity across the narrative. But for Ozu, the combination of these techniques results the opposite, presenting a self-aware and emotionally-intense everyday scenario which builds upon a direct conversation with the audience. The usage of these cinematic techniques continues to be an inextricable part of Ozu’s cinematic language through his entire film career, embodying his philosophy of straddling the realm of subjectivity and objectivity, and offering contemplative cinemas to viewers not only to realize the sadness and melancholy about the reality of life but to retrospect their own experiences.